Revolution at the RA: a message for our times

Isaak Brodsky, V.I.Lenin and Manifestation, 1919

Oil on canvas, 90 x 135 cm

The State Historical Museum

Photo © Provided with assistance from the State Museum and Exhibition Center ROSIZO

Revolution at the RA: Compelling art with a message for our times

“Simple solutions to complex problems”: in 2016, this (ironically simple) refrain became a common criticism laid at the feet of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump.

From 11 February-17 April the Royal Academy is looking back on one of the most momentous and transformative periods in modern history with Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932. One hundred years on from the start of the Russian Revolution, we see some of the most startling examples of “people’s art” and propaganda images in history. But what, if anything, does Russia’s revolutionary art have to tell us about populist politics today?

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Fantasy, 1925

Oil on canvas, 50 x 64.5 cm

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

“Simple solutions to complex problems”: in 2016, this (ironically simple) refrain became a common criticism laid at the feet of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump. It managed to encapsulate everything his opponents hated about him. While experts responded to the issues of the day with “It’s complicated, difficult and fraught with ethical dilemma”, Trump said “I’m a smart man”. And succinctly completed his run for presidency, in his inaugural speech, by bellowing “America First”.

As alarming as the world has found the first weeks of Trump’s presidency, the political rhetoric he relies upon is as old as time itself. His use of binaries to frame a world view based on good versus bad, smart versus dumb, has resulted in an American electorate more sharply polarised than ever before. His argument invariably rests on a question so simple it’s elegant: “Do you love your country or not?” The nation in crisis falls back on an old formula; in the weeks following 9/11, President George W Bush told the world, "Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."

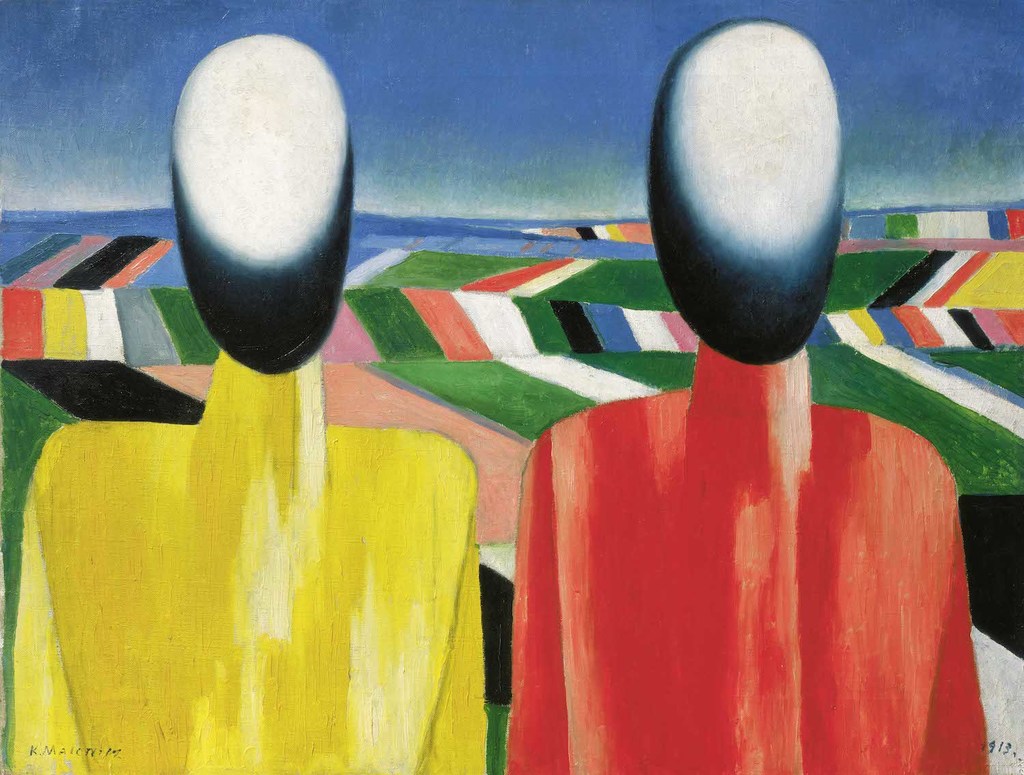

Kazimir Malevich, Peasants, c. 1930

Oil on canvas, 53 x 70 cm

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Political entities throughout the ages have won success by stoking this fire of nationalism and populism, and from Mount Rushmore to Shepard Fairey’s ‘Hope’, the propaganda image has been crucial. Consider the now-infamous ‘Pocket Miliband’ ad, created by M&C Saatchi in 2015, which successfully convinced English voters of the threat of Scottish power through its clear and powerful symbolism. Some argued this image alone was enough to change the course of the election.

The same Saatchis are responsible for the 1996 ‘Demon Eyes’ ad, run by the Conservative Party – a campaign so bold and controversial it was deemed unacceptable by the Advertising Standards Authority (Maurice Saatchi was later awarded a life peerage by the Conservatives). These campaigns have proved time and again that a picture is truly worth a thousand political words.

While the political image dates back thousands of years, from stone carvings to the Bayeaux Tapestry, propaganda art as we know it was born in the First World War. It was in 1914 that Lord Kitchener first told young men he wanted YOU, launching a new trend in art that would later serve as the basis for many kitschy pieces we now find in our high street homeware stores and student flats. With their patriotic block colours and emotive messages (“FIGHT FOR THE DEAR OLD FLAG”), the designs brought forth by the British Propaganda Bureaux moved thousands to take up arms and lay down their lives for Queen and country.

It was in 1914 that Lord Kitchener first told young men he wanted YOU, launching a new trend in art that would later serve as the basis for many kitschy pieces we now find in our high street homeware stores and student flats.

Boris Mikailovich Kustodiev, Bolshevik, 1920

Oil on canvas, 101 x 140.5 cm

State Tretyakov Gallery

Photo © State Tretyakov Gallery

But, as seen at the Royal Academy’s moving exhibition, Propaganda Art was given new life in 1917, when Russia’s October Revolution saw the Bolsheviks take power. From this period came some of history’s most striking propaganda imagery, avant-garde and revolutionary in its own right.

The dramatic images on show in this powerful exhibition evoke heroic realism and the nostalgia of proletariat culture, glamourizing the common worker. Awash with muscular, clenched fists and bright-eyed women in babushka scarves, they served to stir the spirit of millions and have an undeniable allure even today. Avant-garde abstracts like Kazimir Malevich’s 'Woman With Rake' (1930-32) use colour and geometric lines to give new life to the peasant, while Boris Kustodiev’s 'Bolshevik' is curiously alarming and empowering at once, a towering worker standing tall over society’s masses.

El Lissitzky’s groundbreaking Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) is, perhaps, one of the era’s most astounding pieces from the early period: violent and aggressive but starkly simple, it reduces decades of political unrest into a single story, told with just two geometric shapes. For propaganda to be effective, it must reduce a complex issue to its simplest form. Us and them. Red and white.

For propaganda to be effective, it must reduce a complex issue to its simplest form. Us and them. Red and white.

Marc Chagall, Promenade, 1917-18

Oil on canvas, 175.2 x 168.4 cm

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

© DACS 2016

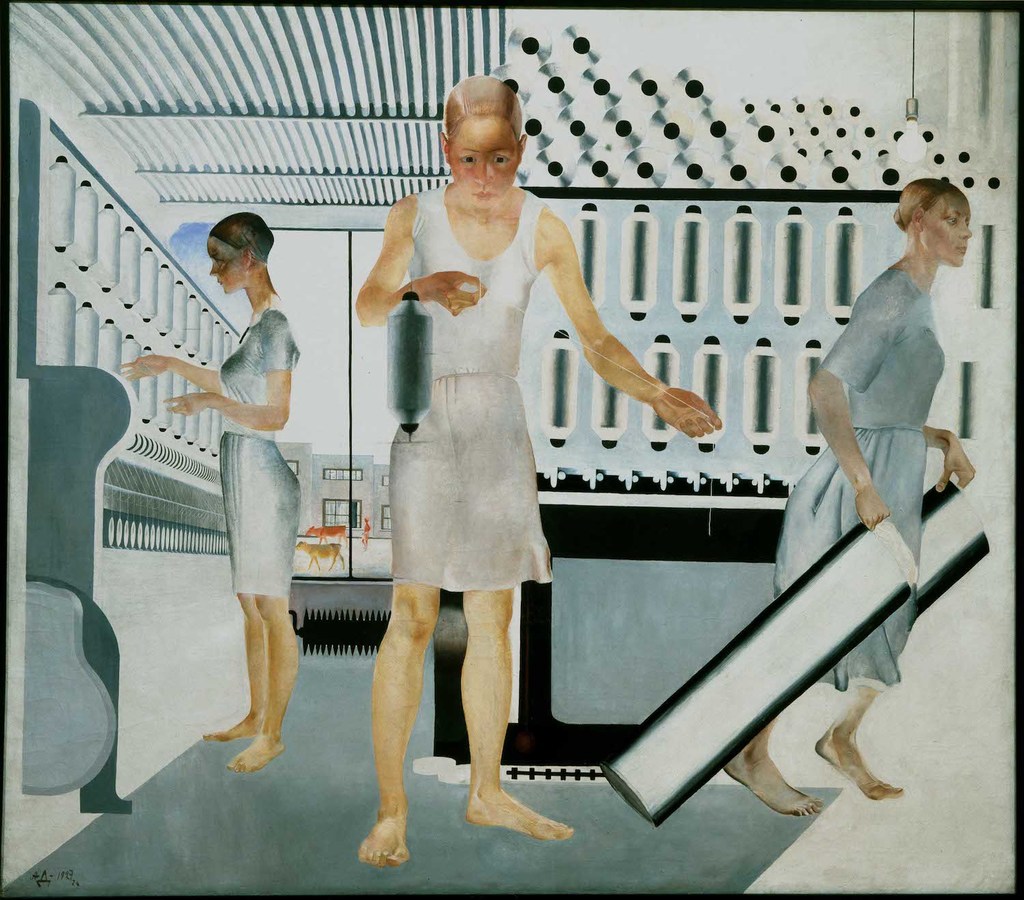

In a time of great political unrest, it’s difficult to avoid the feeling we’re being told something here. You’ll find a heady mix of traditional portraits alongside Kandinsky’s enticing abstract pieces like Blue Crest (1917) and, of course, brutal propaganda. The narrative of the exhibition ends in a section called Stalin’s Utopia, where darkly unnerving pieces like Alexander Deineka’s Race (1932) remind us of Stalin’s vision for a unified, idyllic and collective society. By now, the avant-garde constructivists of the revolution have been replaced by state-approved artists who faithfully toed the Communist line. More traditional and less overtly political, they instead tell a political story with young, healthy athletes and workers who are a vision of Stalinist success.

The romance and nostalgia of the period remains palpable, because these pieces tell us little of the famine, imprisonment, exile and murders that were a reality for thousands in Russia. They remind us of the power of political messages to move minds and change hearts, and of the impact of political events on our artistic and cultural world. The globe is already stirring, with protest movements from the ‘Womens March’ on January 21st to the growing ‘Resist’ movement in America, gathering force. From the optimism of the early period to the brutal authority of the latter, crushing liberal dreams, the compelling narrative of the exhibition may seem to some like a warning for today, and a call to take action.

By Hollie Pycroft.

Alexander Deineka, Textile Workers, 1927

Oil on canvas, 161.5 x 185 cm

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

© DACS 2016