What Makes a Man?

Fragile. Toxic. These words have been filling column inches of late. They suggest that masculinity would be dangerous to the touch — easily harmed and/or harmful.

But the subject is not held at arm’s length at Barbican’s Masculinities: Liberation through Photography; the first work you encounter upon walking in is immediately tactile. Across four large panels, John Coplans’ Self Portrait (1994) shows deflated bum cheeks, elbow creases, stomach folds, sagging pectorals, and wiry hair.

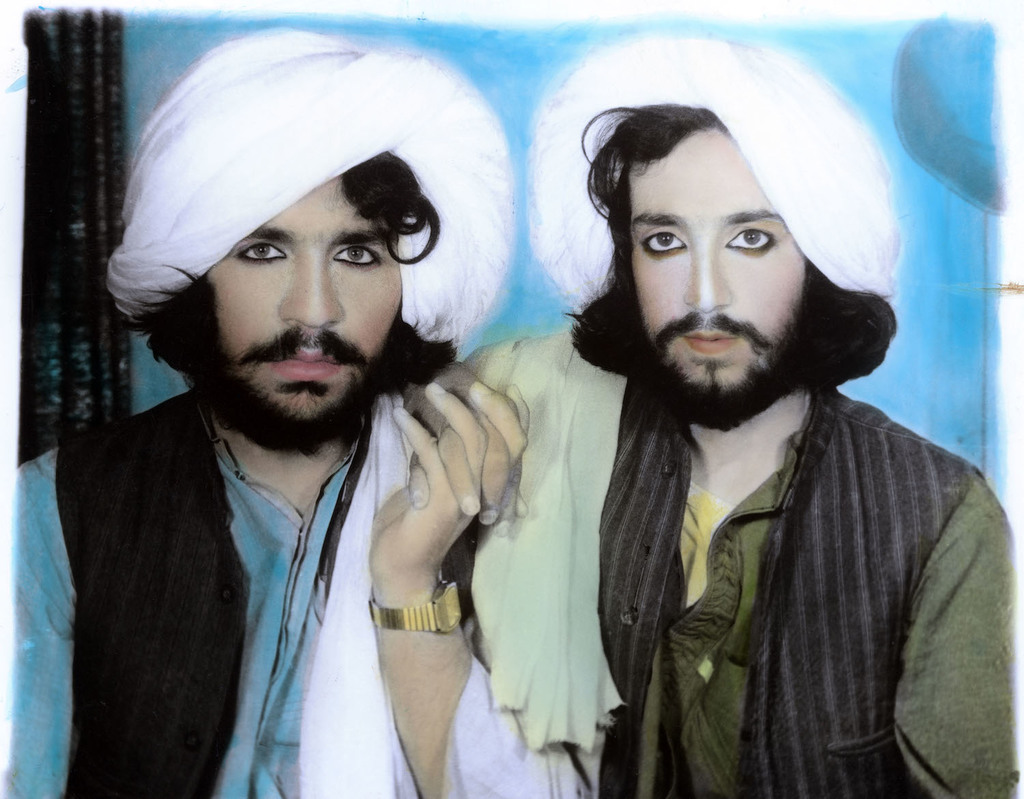

Taliban fighters, discovered by Thomas Dworzak in the back rooms of Kandahar photo studios: against colourful backgrounds of hand-painted haloes and flowers, the soldiers pose, some holding hands, their eyes lined with black kohl.

John Coplans’ ’Self Portrait’ (1994). 'Masculinities : Liberation through Photography', Installation view, Barbican Art Gallery - 20 February 2020 – 17 May 2020 ©Tristan Fewings / Getty Images

Three photographs make up each panel and at first glance seem to have been cut from a single image. But minute misalignments and slight variations in scale reveal the body’s fragmentation. Tightly framed, the composite naked figures seem like they only just about fit within the confines of the white grid — just as this ageing, vulnerable body (and with a softness we more typically associate with female bodies) is somewhat difficult to square with our conception of the strong and powerful male archetype.

Indeed, Disrupting the Archetype is the first section’s title. Here we find images of Taliban fighters, discovered by Thomas Dworzak in the back rooms of Kandahar photo studios: against colourful backgrounds of hand-painted haloes and flowers, the soldiers pose, some holding hands, their eyes lined with black kohl.

Thomas Dworzak 'Taliban portrait. Kandahar, Afghanistan.' 2002. © Collection T. Dworzak/Magnum Photos

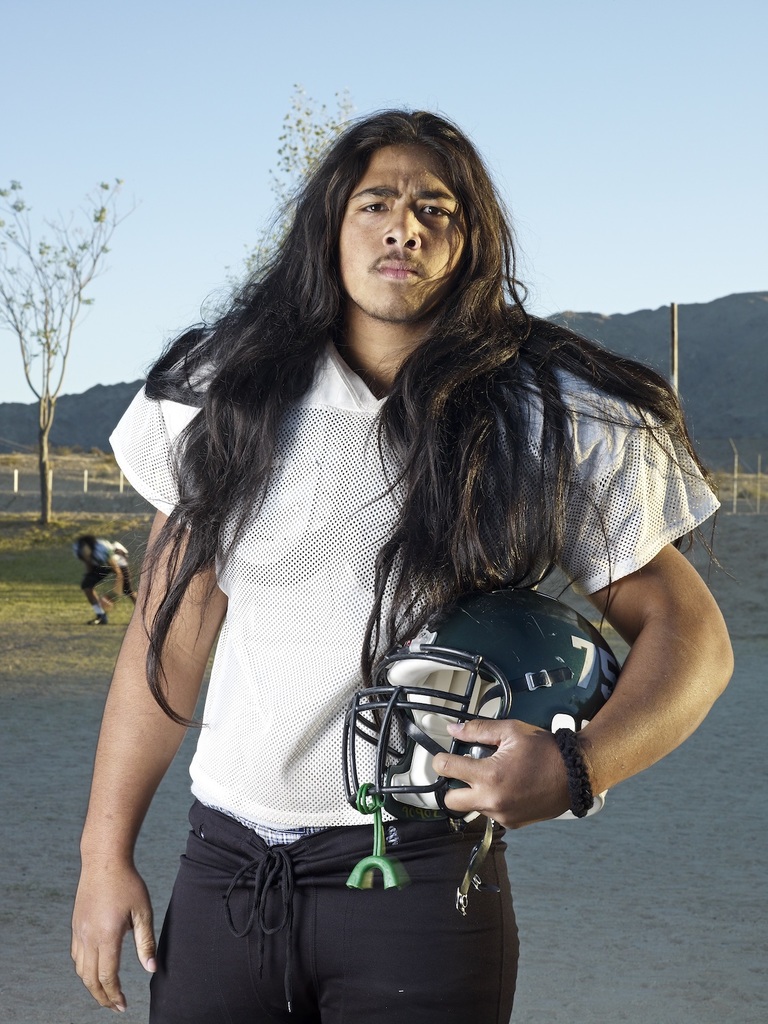

Amidst bodybuilders, cowboys and high-school football players with shoulder pads bigger than their heads (image below - Catherine Opie's Rusty, 2008) are Rineke Djikstra’s Bullfighters (1994, 2000). Shot against neutral, indistinguishable backgrounds, the photo series has a painterly quality; the blood on the forcados’ faces and the lapels of their flowery jackets could be daubed on with a brush. While this blood signifies courage and the reckless violence of their vocation, searching the faces of these four bullfighters for further context reveals a vulnerability, both in their youth and exhausted poses.

While this blood signifies courage and the reckless violence of their vocation, searching the faces of these four bullfighters for further context reveals a vulnerability, both in their youth and exhausted poses.

Rineke Djikstra’s ‘Bullfighters’ (1994, 2000) on r-hand side. 'Masculinities : Liberation through Photography' Installation view, Barbican Art Gallery - 20 February 2020 – 17 May 2020 ©Tristan Fewings / Getty Image

Becoming bloodied by battle is the exception that proves the following rule: the male body shouldn’t leak. Not publicly, for any length of time. Yet here’s Knut Asdam filling the screen with a clothed male crotch; a dot appears in the man’s trousers, then widens, spreads to a dripping wet patch. Untitled: Pissing (1995) couldn’t be named more aptly: flattened anonymity prevents us from identifying with the man behind the trousers, while close proximity challenges us to confront embarrassment in a vacuum, the pleasure of relief, and the loss of control. Also leaking is Bas Jan Ader in I’m Too Sad to Tell You (1971). The artist is crying, but as we’re given no knowledge of why, the scene is poised between melodrama and sincerity. Is this healthy release — or is it, as critic Jennifer Doyle suggests, a reiteration of white male melancholy, the ’male artist as emotionally injured’?

Catherine Opie 'Rusty', 2008 © Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

While these works subvert masculine ideals that have the potential to produce harmful effects, Anna Fox’s work gives toxicity a more intimate, concrete treatment. My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words (1999) is a series of small photos. We have to get close to see detergents, plates, wrapping paper, all stacked neatly in claustrophobic cupboards. Accompanying the images is text, set in a wedding invitation’s calligraphic font, smaller still. 'I’m going to tear your mother to shreds with an oyster knife', reads one caption. 'I am going to cover her in grease and fry her,' says another. The cursive typeface, dissonant with its content, suggests how readily we smooth over such threatening behaviour, normalise it; boys will be boys, etc. Here patriarchal violence, displaced into housework, patterns the minutiae of everyday life.

Fragmentation underscores the marginalized position of LGBTQ figures throughout much of art history; and concealment of the eroticised scene here is not so much to hide it, as to make the viewer aware of her ambiguous involvement in it — and how does it feel for you to be the outsider?

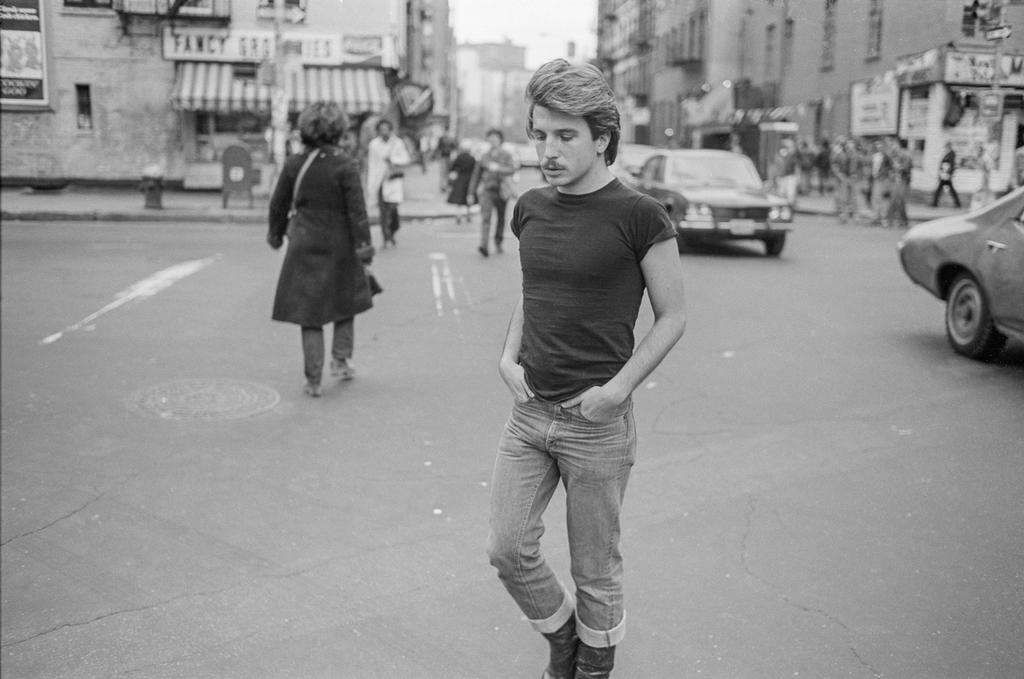

Sunil Gupta 'Untitled 22 from the series Christopher Street, 1976.' Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery. © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

While downstairs largely explores and undermines hegemonic masculinity, upstairs focuses on other more marginalized ways of being a man. Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s Studio (0X5A0173) (2017) is a deconstructed black male nude — though the nudity is occluded by prints of already existing photographs and pornographic cartoons. In actual fact, we can only see the man’s arms: one hangs casually by his side, while the other points a camera back at us. Sepuya’s nearby works are similarly palimpsestic, layered with (notably) black velvet (for sensual black skin) and cameras that keep our voyeurism in check, as if collage and cover weren’t enough.

Unlike some of the photographs I’ve already mentioned, Sepuya is not so much subverting hegemonic masculine archetypes as those of studio portraiture, constructing queer identities in all their multiplicity. Fragmentation underscores the marginalized position of LGBTQ figures throughout much of art history; and concealment of the eroticized scene here is not so much to hide it, as to make the viewer aware of her ambiguous involvement in it — and how does it feel for you to be the outsider?

Rotimi Fani-Kayode 'Untitled,' 1985 © Rotimi Fani-Kayode Courtesy of Autograph, London

Rotimi Fani-Koyode is another photographer using fragmentation to evoke the experience of outsiders — and Bronze Head (1987) is a powerful image of sexual and diasporic exile. It shows splayed buttocks squatting over the head of a Yoruba god, whose pupilless bronze eyes engage the viewer, in a similar manner to Sepuya’s camera lenses. The buttocks appear sculpted as a classical Western statue, while the bronze icon, the real sculpture, alludes to the ‘technique of ecstasy’, a form of mind alteration used by Yoruba priests to communicate with the Gods — metaphysics balanced by raw physicality, and vice versa. Here ‘ecstasy’ has been demoted to pleasure, but the gesture isn’t merely irreverent — through its transgression, ‘Bronze Head’ posits a different kind of faith, perhaps faith in oneself, despite displacement and the loss of wholeness occasioned by exile. Photography is not just an artform, but ‘a weapon,’ Fani-Koyode writes, ‘if I am to resist attacks on my integrity and, indeed, my existence on my own terms’.

'Masculinities : Liberation through Photography Installation view,' Barbican Art Gallery - 20 February 2020 – 17 May 2020. ©Tristan Fewings / Getty Images

We all too often think that we are our gender, I am a man. It’s much trickier to consider myself as the consolidated impressions of a man, as formed through iteration; that my gender ‘is a performative accomplishment,’ as theorist Judith Butler would say, ‘compelled by social sanction and taboo’. Then, in light of theories like Butler’s and exhibitions like the Barbican’s, it can also be tempting (and perhaps productive in the short term) to go the other way: to think and act as if masculinities can be shrugged on and off, playing a bullfighter one day, a boy the next, and so on.

While masculinities are not always roles we choose – rather, imposed – society still privileges their manifestations over other modes of being. It’s in deviating from them that snarls are prompted from waiting wolves. That’s not to say we don’t have agency; as a society, we can influence what kinds of masculinity we produce. Whether the societal pressure is for men to be tough, or not to cry (or otherwise leak), or to be ‘normal’ (whatever that means) we have the power to resist these impositions on our streets, in our kitchens, or indeed in photographs. Here we have men of few words. But each picture speaks a thousand.

By Sammi Gale