Mourning Marsyas

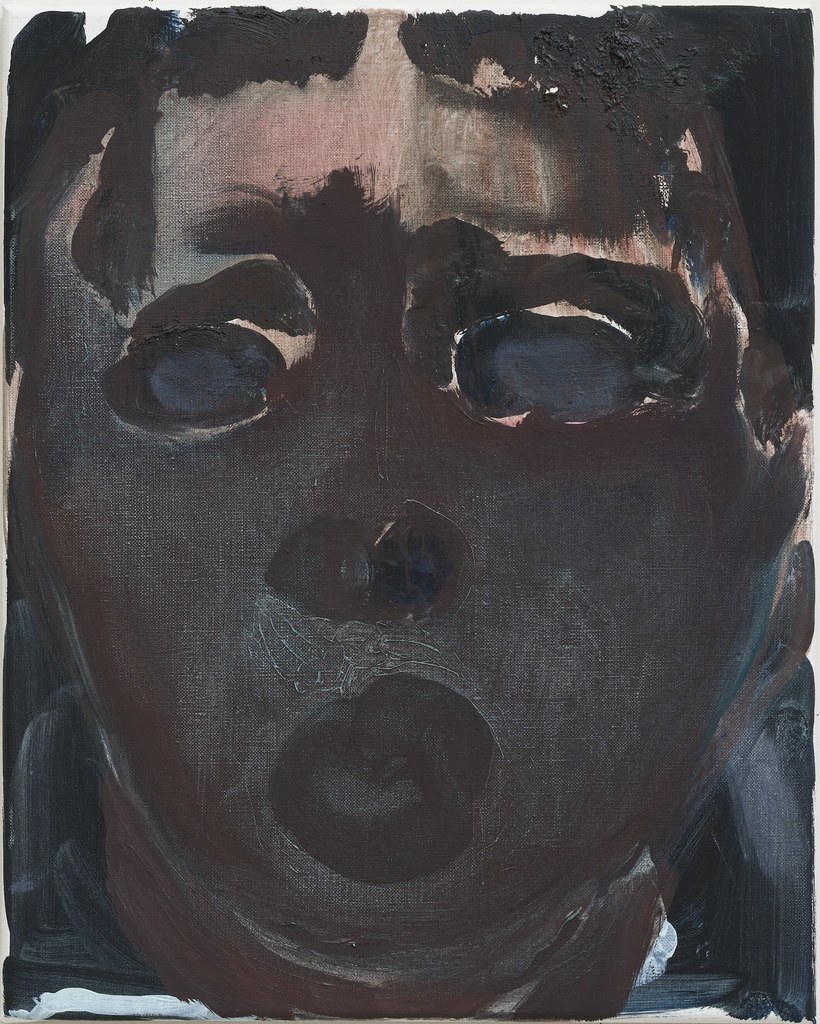

A cavernous pair of eyes swim within an inky puddle of features in Marlene Dumas’ ‘War’. Situated on the ground floor of her solo exhibition Mourning Marsyas at Frith Street Gallery, this intimately scaled painting depicts an intensely close-up face. It is as if the figure is trying to outrun the canvas. The eyes are painted as deep voids, endlessly expressive despite Dumas’ characteristically economical use of form. The work calls to mind countless documentary photographs of victims of war staring down the lens, but the artist abstracts the details. Like many of the paintings in this exhibition, ‘War’ moves beyond physical reality, instead capturing a raw psychological state.

"the exhibition challenges what is seen and not seen; what we choose to look at or avoid"

Marlene Dumas

War, 2024

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 x 2cm

Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Photo: Peter Cox

Numerous pairs of eyes can be found in Mourning Marsyas. They beam out from a host of semi-abstract faces that follow the viewer around the exhibition. Some are full of terror. Others are suggestive of malicious intent. The eyes in ‘Nemesis’ appear as two round swirling dots, sitting uncomfortably far from one another and giving the impression of a face being pulled from side to side. Conversely, ‘Pareidolia’ – titled after the human instinct to see recognisable forms everywhere – is fittingly only loosely indicative of a face and pair of jet-black eyes, formed organically by poured paint. From the gallery’s frosted front, which conceals the paintings from people outside, to the artist’s constant slips into formal vagueness, the exhibition challenges what is seen and not seen; what we choose to look at or avoid.

Marlene Dumas

Mourning Marsyas, 2024

Oil on canvas

300 x 100cm

Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Photo: Peter Cox

Dumas has rooted the show in the story of Marsyas, a satyr who challenged Apollo to a musical competition, on the agreement that the winner could treat the loser in any way they desired. When the god Apollo won, having played his instrument upside down – something Marsyas is not capable of doing – the satyr was flayed alive. The eponymous painting ‘Mourning Marsyas’ sits at the entrance to the exhibition, capturing the horror of flaying without overt gore. In the work, a central hanging figure merges with the watery forms around them. Part of their body, which could be understood as skin or blood, spills out around the feet into the surrounding canvas.

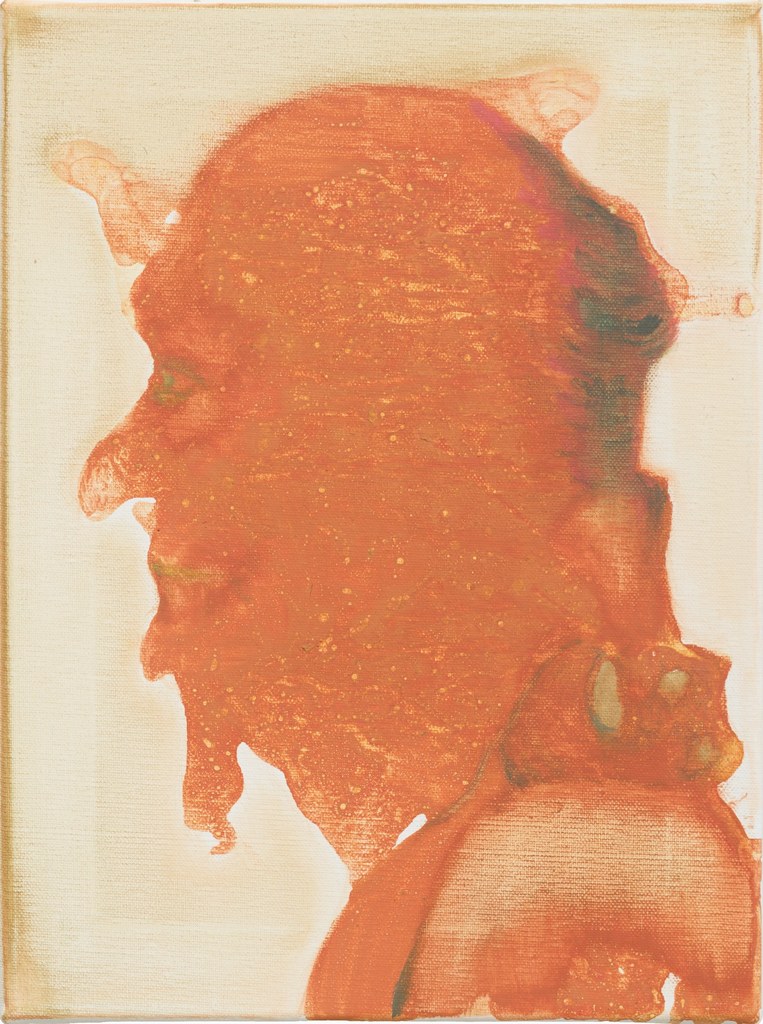

Marlene Dumas

The devil may care, 2024

Oil on canvas

40 x 30cm

Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Photo: Peter Cox

"Dumas sees the satyr as a symbol of hopeful ambition and creative freedom, who speaks truth to power"

While this parable provides a conceptual starting point for the exhibition, the power dynamics and emotions in the paintings can be understood on many levels. Apollo’s might gave him unfair advantage in the competition, and he reveled in the opportunity to cause agonising pain for Marsyas. Dumas sees the satyr as a symbol of hopeful ambition and creative freedom, who speaks truth to power. Similar moments of cruelty and abused hierarchy are explored throughout the exhibition, sometimes in connection with specific, horrific historical events. At other times, the artist leaves it to the viewer to interpret possible expressions of pain or viciousness; to distinguish between perpetrator and victim. While the majority of the paintings feature human figures, she has included other icons of oppression. ‘Two God’ cheekily plays with the potency projected onto the penis, depicting two hefty erect phallic forms squashed into the canvas.

Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery.

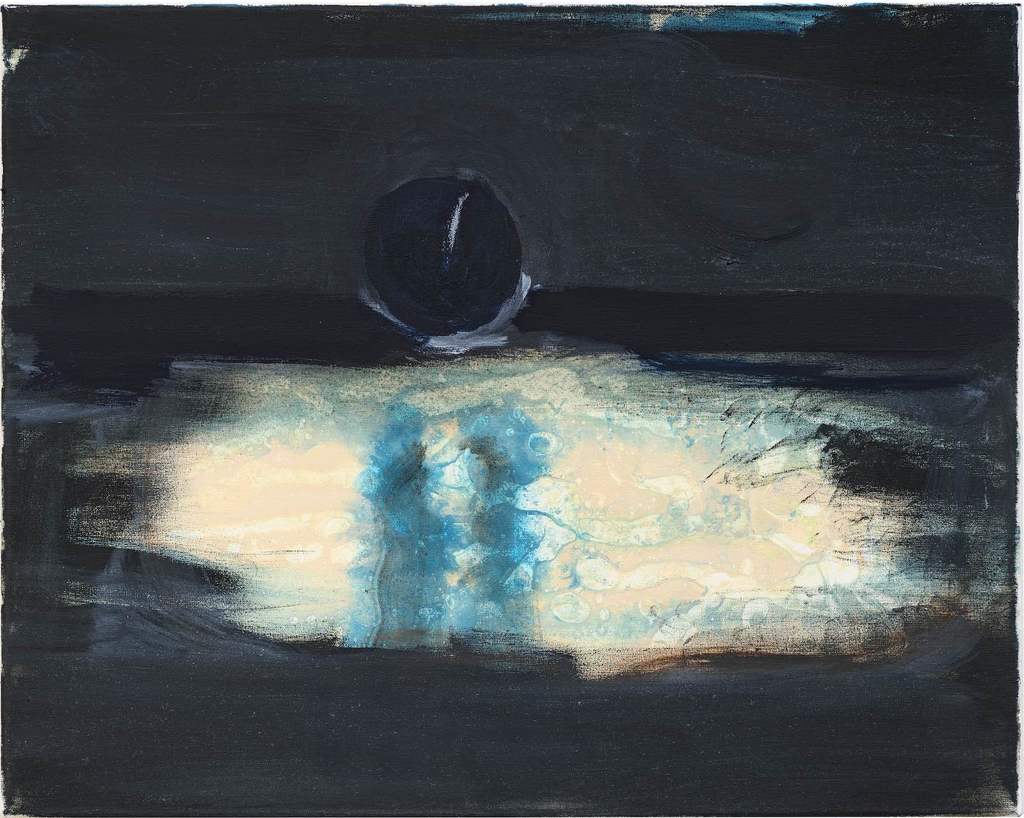

Dumas relishes the sinister potential of language. Work titles such as ‘Last Man Standing’ and ‘The Devil May Care’ play with well-worn phrases, whose familiarity usually renders them devoid of specific meaning. Their use here invites reconsideration. For example, the haunted features and dark ringed eyes in ‘Last Man Standing’ suggest a violent backstory. The phrase is often used to refer to the winner of a fight or race, but in this image, he seems to be the only survivor of a catastrophic event. The simple title ‘Ceasefire’, which depicts a pair of figures standing in what looks like a pool of blood, immediately conjures the millions of cries for an end to Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. What at first felt like a potent call to action has, over the last year and in the face of unrelenting force, been stripped of hope to some degree. Other titles speak directly to historical brutality. ‘Makapansgat Pebble’ reflects upon the Ndebele chief Makapan, who was starved to death by the Boer commando in 1854. This waterworn pebble was found inside the cave he and his people were barricaded within, amongst their bodily remains. The marks on the rock itself allude to a face, which has borne witness to atrocities. Elsewhere, ‘Utøya’ reflects upon the 2011 Utøya massacre near Oslo, taking inspiration from the work of Edvard Munch.

Marlene Dumas

Utøya, 2018-2023

Oil on canvas

40 x 50cm

Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Photo: Peter Cox

These highly specific moments melt into the space around them. The artist focuses upon snap shots of extreme violence and oppression temporarily, before journeying the viewer to another moment in time. Given similar treatment, the parallels between these acts come to the fore; cases of supreme injustice, in which one party sadistically overpowers the other. It evokes a cruelty that spills through history, not from gods onto humans, but from man to man. The viewer is left as a somewhat helpless witness. Dumas has called painting an act of mourning, describing her works as ‘heavy with the weight of a bad conscience, deceased lovers, past failures and present atrocities’. In psychoanalytic terms, mourning involves the loss of the object – or deceased loved one. The primary goal is to detach from the lost object and accept that it has gone. Yet, Dumas’ paintings plunge viewers into her watery world, evoking a never-ending sense of mourning. They are both a reminder of our own detachment, and a potent challenge to keep connected.

By Emily Steer