Art under Brexit

Art in a Windowless World

The British government could have decided to release fifty lions into the streets of Brussels to announce its departure. Fifty MEPs and their clerks could have jumped to their deaths from the European Parliament.

Britain enters a world without space. You can call Brexit whatever you want – an entirely reasonable reaction to all the inhuman logics of globalised capitalism, the heroic individualists pulling themselves out of bureaucracy and corruption, a sneer at the polyglot neighbours, the old desperately grabbing at their imagined past – and not be wrong. Brexit was a ‘no’, and negating something always carries the infinities of everything else. But this isn’t what we’re getting. What we’re getting is tautology.

Ever since the referendum, the government has been busy foreclosing possibilities. Brexit, we’re told, means Brexit: everything has to mean precisely itself. We are about to become a ‘truly global Britain’, and it should be taken at face value: not Britain within the globe, but a globular, rounded, edgeless Britain, its landscapes groaning and buckling as the corners close in on each other, sealing together, and becoming perfectly round, so you can walk desperately through the fields forever until eventually you come right back to where you started. No way out, and no way in. The entire country has taken on an unspoken nihilist ideology, a constant drizzling hatred for all life. We talk about the burden of migration, having to cope with however many new arrivals, the drain on common resources that each of them represents. In other words, the human being is both excess and negation, something distressingly more than it ought to be, something less than a presence, something that ought not to exist at all. Every person is a void, sucking up food and jobs and healthcare that could have gone to someone else. In a post-industrial society, our dominant economic activity is no longer production but consumption, and politics lacks a language for all the other ways in which any person can add to the world: all it can see is a ravenous jaw and a shitting anus, a despoiler, a locust. A locust can be quantified; a locust can be understood.

There’s a slow and creeping war against the imagination, fought trench by trench, digging in to every open space of meaning and cutting down to the solid self-identities. Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty gives no indication of how the notification is actually meant to be delivered; it’s according to whichever constitutional mechanism the country in question chooses. We could have done anything. The British government could have decided to release fifty lions into the streets of Brussels to announce its departure. Fifty MEPs and their clerks could have jumped to their deaths from the European Parliament. At the very least we could have waved an enormous flag from the cliffs of Dover. Instead, with every option available, we chose to write a letter, and have it hand-couriered to Donald Tusk. A glorified invoice. With the dancing lies and tragic deaths of the referendum gone, the national future is now being decided by paperwork. Doors closed, shutters sealed, the stifling spacelessness inside. We communicate through hand-written notes passed through the cracks; the rest of the time, it’s silence, sullen and ungrateful.

How are you meant to create art in a windowless world?

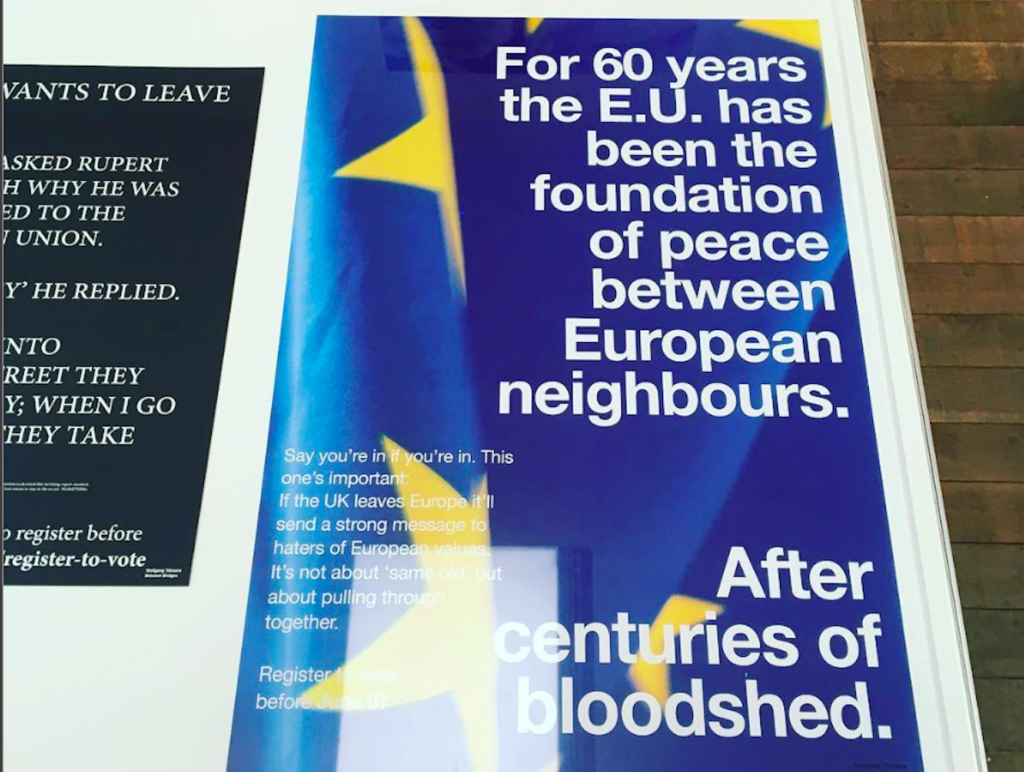

Wolfgang Tillmans at Tate Modern, exhibition shot.

The basics are already known: on its most material level Brexit will be bad for art. All the money that Britain sends to the EU will, from now on, be kept for ourselves. The lie was that we could use it to benefit our own people instead of Romanians or Portuguese; the likely truth is that it won’t be used for anything at all. It’ll be put against the deficit, dwindling into nothing for the benefit of a credit rating and a few numbers on screens. Something like €1.5 billion of funding for the creative arts will vanish: how could we, alone now, justify putting so much money into something so fiscally useless? Galleries will close, films will go unmade and books unwritten.

But art isn’t just made out of money; great artists have worked in hostile and reactionary times. But something else is going; the possibility of a possibility. As Theodor Adorno noted, the plastic arts open up unseen spaces in the world, small vacuoles of a freedom that’s crushed everywhere else: the flat surfaces of paintings open up onto a vastness that isn’t entirely illusory, the infinite depths in which you can remake the world as you want. Music does the same to time, holding it suspended, releasing it all at once, annulling it entirely. It’s prefigurative; to really take back control would mean extending this freedom into all areas of life. The assault on the imagination doesn’t just consist in refusing to fund it; it’s the abolition of open space entirely.

Art is difficult to understand, and just like the voices of all those foreigners talking on public transport, in our closed-in future everything that can not be understood is forbidden.

See Theresa May’s scorn for the ‘citizens of the world’ or the people who live ‘nowhere’, the in-between spaces, the spaces that create themselves. Everything must be rooted in place, not extending in space; bolted down, growing spindly out of a tired and vanishing earth. The assault is everywhere, because everywhere is reduced to the same pedantic here. In politics: monoculturalism and chauvinism, violence against migrants and refugees, the refusal of the outside world. In language: tautology, blithering common sense, received wisdom, the refusal of the indeterminacy of the signifier. In culture: nostalgia and witlessness, the refusal of the reservoirs of what is not understood. Take a line from a Daily Express comment piece: ‘like EU bureaucrats in denial about Brexit, curators fail to acknowledge the disconnect between artists and their audience, blaming ignorance or prejudice for a lack of appreciation.’ Art is difficult to understand, and just like the voices of all those foreigners talking on public transport, in our closed-in future everything that can not be understood is forbidden.

As a kind of compensation, we get the sea. ‘If Britain must choose between Europe and the open sea,’ Winston Churchill is supposed to have said, ‘she must always choose the open sea.’ The line is repeated like an incantation; we will bring this open sea into being. Britain is unusual here: in most countries, it’s the coastal areas that are most liberalised and open-facing, turning towards the rest of the world. (This isn’t without its negative articulations: see, for instance, the reflexive class chauvinism of coastal Americans towards the scrunched-up bigots in Flyover Country.) Here it’s different; the seaside is where the reactionaries live, hurrying along the rain-clammy pebbles that slope into an indistinguishable grey wash with nothing on the other side. The post-Brexit plans tend to have a strange naval obsession: we were once a mercantile power, trading back and forth across the Atlantic (it’s best not to think about exactly what – or who – we were trading in); after we leave Europe and its cloistered creatures of the land, we can do it all over again. There are plans for trade yachts, floating embassies to plough through the waves, hawking our financial services and our advertising agencies and our jam. Britannia rules the waves: because this country has always been a naval power, it’s incapable of seeing the ocean as its other; there’s no sense of its vastness or the monsters and mysteries that live underneath, it’s of a piece with the folded misery of the land. In Britain, the sea is just melted profit.

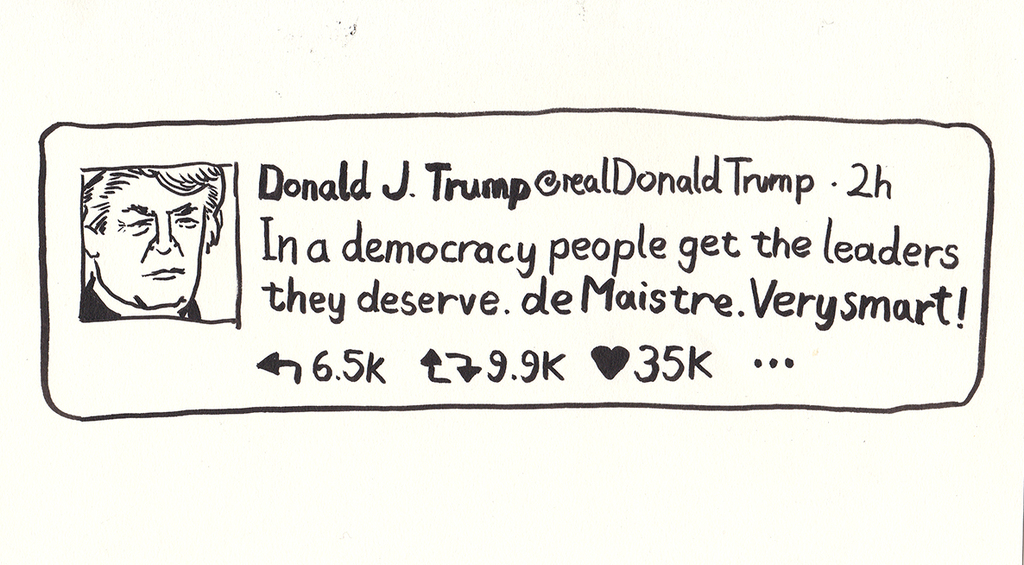

Cartoon by Gary Zhang

But if there’s any hope for art, it’s here. The great painter of the sea was Turner; as John Berger writes, it’s Turner who ‘represents most fully the character of the British 19th century’ – the hideous and genocidal time of empire and stupidity, in which open space was devoured in pink-tinted maps and the whole world was processed into a giant version of the bourgeois Englishman’s comfortable home, with the women imprisoned in its heavy walls and the poor dying at the gates. But Turner’s sea-paintings are never proud, or heroic: what he shows are innumerable apocalypses, the aftermaths of crimes, the slaves drowning overboard as the sun rages gorgeously overhead. All these figures are clear and brutal and despicable, but in so many scenes the sea can never quite fill the frame: it falls apart into dribs and splotches that mark the edge of the real painterly infinity that extends far out in all directions. The sea always changes; the space in which a better world is growing is out there, over the horizon. If art survives Brexit, it starts by standing, with your back to the land behind you, and look out at the emptiness that is never simply what it is, and is never simply understood.

By Sam Kriss.