All this is particularly fertile ground for someone who paints portraits; Joffe treats the ‘prince’ not as an inherited title, but as a mood — a gesture — a way of being. 'I like the idea that being a prince can mean a lot of things,' says Joffe. Indeed, the exhibition consists of two distinct but interconnected bodies of work: four large-scale portraits of Joffe’s partner, Richard, and a series of portraits of the writer Charlie Porter. Scattered among these are smaller studies: Frazer, a young boy affectionately nicknamed the ‘Disney prince’... Olivia Laing, dressed in royal costume for a school event... and Lee Mary, a New York-based artist who also carries a princely air.

Share this article

Chantal Joffe’s Princes

Chantal Joffe’s new exhibition at the Exchange Gallery in Penzance asks what it means to be a prince. It’s a question that might feel distant to those of us not born into royalty, but embedded within it are broader considerations of how men are seen — and how they see themselves. A prince is crucially not yet king, his role still in formation. As such, ‘princeliness’ is a performance — learning how to be looked at, testing different versions of oneself in the mirror of another’s gaze.

Chantal Joffe, Charlie 3 - Fluffy Coat, 2023. ©️ Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

"princeliness is a performance"

Chantal Joffe, The Prince, installation view, showing at The Exchange, 15 May – 1 Nov 2025.

‘I wanted to make a show that didn't demonise men but talked about masculinity and what it is, what it can be, and in a loving way.’ In Joffe’s hands, masculinity is neither fixed nor singular — it becomes tender, uncertain, even playful. Her princes don’t dominate; they dwell, reflect, falter, and sometimes fold laundry.

The prince, historically, is as much a performance of elegance and restraint as of authority. Here, that performance is more nuanced. There’s a desire to slip free from the gaze — to resist being fixed by admiration, expectation, or even love—that runs through Joffe’s paintings. Her sitters feel at ease, almost unselfconscious. Her painting style — loose, expressive — creates the impression her sitters are posing but not pausing, still mid-thought or mid-movement. There’s no theatricality, more so a quiet immediacy. Expressions are caught and bodies tilt and shift as if caught between gestures and conversations.

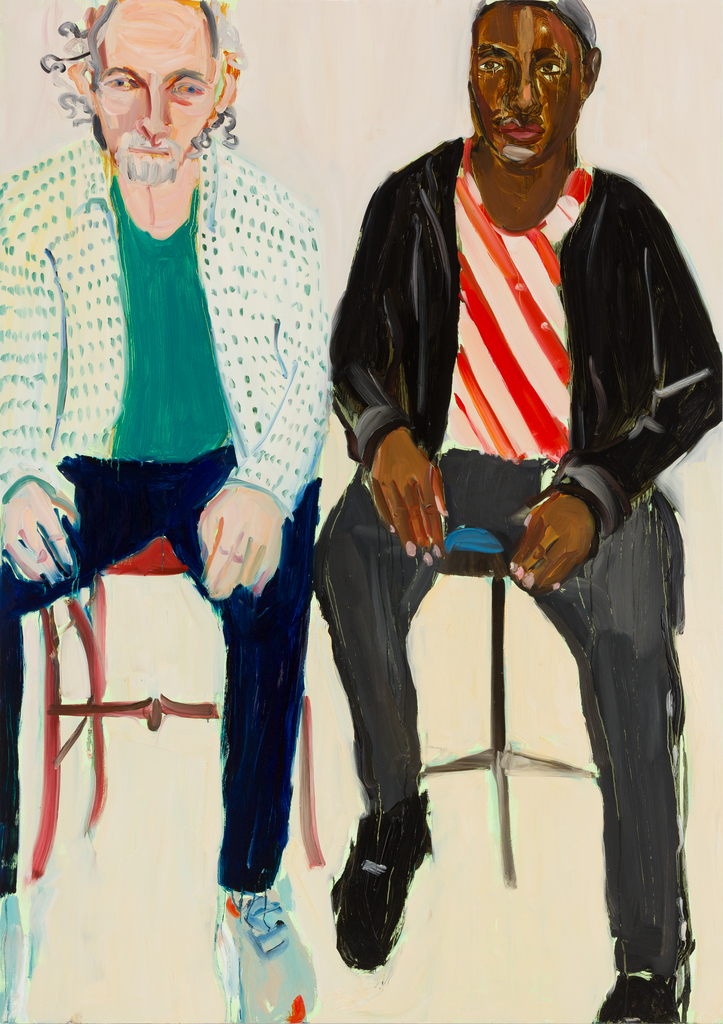

Chantal Joffe, Harun and Richard, 2024. ©️ Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

"I wanted to make a show that didn't demonise men but talked about masculinity and what it is, what it can be, and in a loving way"

'People who sit for me often ask what they should wear,' Joffe says. This question is simple on the surface — but of course clothing reveals a lot: not just about style, but about character, mood, vulnerability — taste. ‘The only thing I ever say is, maybe not jeans. They're quite dull to paint, in all honesty.’

Chantal Joffe, Charlie 2, 2023. ©️ Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

A handmade garment — as in the case of Charlie Porter, who appears in the show in clothing he designed and made himself — carries its own intimate charge. Joffe painted her friend during a time when both had recently lost their parents. In these works, the language of fashion becomes central. His sensitivity to the shape, colour, and texture of fabric feels instinctive — a sensitivity mirrored in Joffe’s seemingly quick and casual brushwork. In one portrait, Porter wears a turquoise T-shirt punctuated with pink patches. In another, he’s enveloped in a Hamlet-esque black suit. ‘He looks like a prince in these clothes’, Joffe says, referring to a painting where Porter wears a white, fluffy coat. ‘The extraordinary fabrics and shapes and their uniqueness to Charlie because he only made one, for himself.’

Chantal Joffe, The Prince, installation view, showing at The Exchange, 15 May – 1 Nov 2025.

"Joffe offers a soft counterpoint to the heroic male nudes of art history"

Richard’s portraits explore intimacy differently. He’s painted nude, reclining, or caught in quiet acts — occupied with the housework, lying down, listening to music. 'We didn’t have to talk, which was nice,' Joffe says. ‘We listened to the Goldberg Variations on a loop. It became kind of meditative.’ That rhythm; the looping of the Goldberg Variations, seeps into the paintings, echoing the repetitive nature of domestic life Joffe is depicting. The paintings do sort of pulse, too; expressions are caught and rendered with a looseness that suggests movement held just long enough to be stilled. Broad, sweeping marks contrast with finer, more deliberate lines.

Chantal Joffe, Richard Naked 2, 2023. ©️ Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

With Richard’s nakedness, Joffe offers a soft counterpoint to the heroic male nudes of art history — a figure at rest, turned inward, even ironing. 'Another gentle thing,' she reflects, 'this naked man focusing very hard on getting it right.

‘The ultimate prince is someone who’s comfortable in their own skin,’ Joffe explains, nodding back to the painting of Richard ironing. ‘That’s a very courtly quality, I think — to be at home in your own skin.'

Chantal Joffe, Charlie and Rich 7 - Summer, 2023 ©️ Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Comfort, of course, is complicated. The idea of being ‘at home’ in one’s body carries different weight depending on who you are — how you’ve been seen, and how you see yourself. For some, embodiment comes easily. For others, it can feel like a lifelong negotiation. Joffe’s work doesn’t shy away from this. She embraces princeliness not as a fixed archetype, but as something evolving — much like the subjects themselves.

Joffe doesn’t offer answers, and that’s the point. Her princes are neither caricatures of stoic masculinity nor effortless embodiments of modern sensitivity. The show isn’t about performing princeliness, it’s about learning to understand it. It’s not about claiming an identity like some kind of birthright, but about watching it slowly come into view.

By Kitty Lees