Girlfriends and Goddesses

If we’re being honest, what first strikes you about a Lisa Yuskavage canvas is the nudity. Mostly, this condition is reserved for female figures – the artist’s most frequent subject – who tend to be cartoonishly voluptuous in terms of their breasts (especially) and tummies, spindly in their limbs. If that sounds like a description of Tomb Raider or a glamour model, then you’re nearly there but not quite. Yuskavage’s genre of women are wildly ‘female’, but not ‘perfect’; their pendulous breasts point in different directions, stomachs soft.

If we’re being honest, what first strikes you about a Lisa Yuskavage canvas is the nudity.

Deja Vu, 2017, Lisa Yuskavage at David Zwirner

In recent years, the artist has expanded her practice to include paintings of couples; her use of ‘emotional formalism’, in which colour and other interventions are applied to the composition to insinuate expression, finds new material. Yuskavage is widely associated with the re-emergence of the figurative in contemporary painting, drawing on pictorial traditions and conventions in order to both expand and subvert them. Her women in Déjà vu (at David Zwirner’s London gallery) are flagrantly nude and naked, oscillating between identities as sexual objects and agents respectively. I’m calling them Girlfriends and Goddesses.

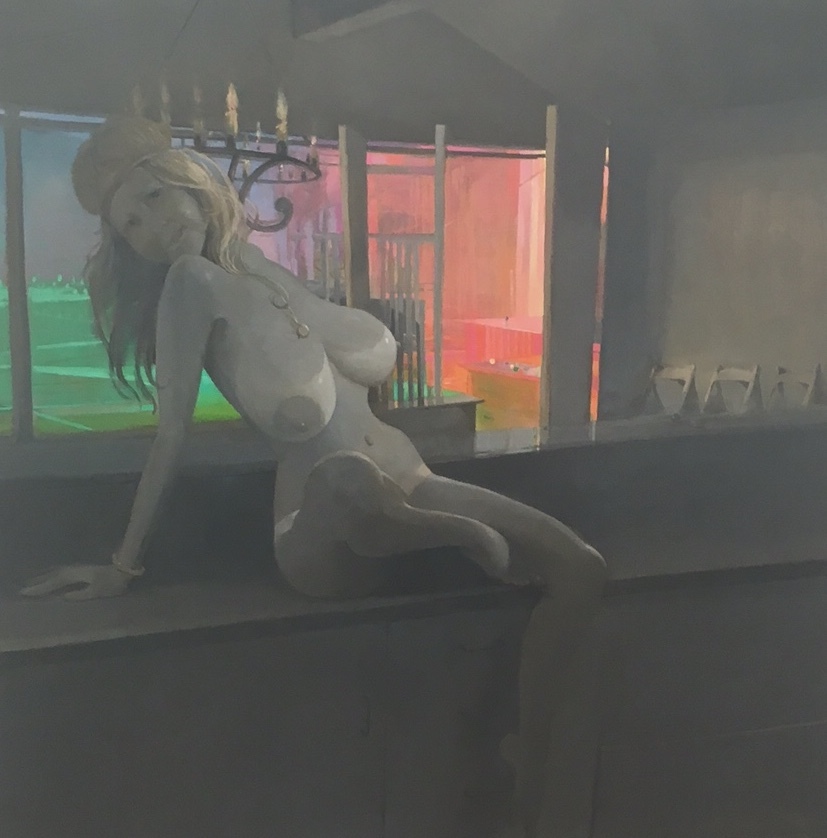

It might feel surprising to discover that these pornographic paintings were made by a woman artist if their style wasn’t so iconic, echoes of them called up by Yuskavage’s name alone. But this isn’t a cut-and-dry case of WOMAN ARTIST REAPPROPRIATES MALE GAZE, or RECLAIMING FEMALE SEXUALITY. It’s more complicated, and a little darker than that. The exhibition’s title image, 'Déjà vu', features a classic Yuskavage figure, her posture and lighting indicative of a kind of preternatural vitality. In perfect technicolour, eyes closed, she stands at once poised and relaxed, loosely resting her hands on the heads of grey, spectral men around her. Is she dreaming them into being? She’s certainly not afraid; however ghostly they appear, they don’t seem to pose a threat. Rather, their grey hue denotes their supplementary status, and makes her all the brighter by comparison. Think of lighting, prominence and power, and move from this goddess to the woman depicted in ‘Housewarming’. She’s smiling blithely, posed like a pin-up: bare chest thrust forward, head cocked and toes pointed at the end of dangling legs, swinging off the counter top of your new kitchen and welcoming you home. If this were a photo, we’d say the lighting was off. The garden, visible through the window behind her, is flooded with colour, while she sits in shadow, catching only glints of sunshine on her left side. It feels like the result of a private photoshoot, an image a man might make of his girlfriend to keep in his wallet, mortified if anyone else ever saw.

Housewarming, 2016, Lisa Yuskavage at David Zwirner

Around half the works in the exhibition fall into this ‘goddess’ category, and although their sexualisation is explicit, they’re not uncomfortable. These are women happy, shy, buoyant in their buoyant bodies. Although their poses insinuate a boyfriend outside the frame, these are not Girlfriends – at least, not in the way I’ll use the term later. They’re touching in their insinuation of a lover behind the imaginary camera, and our vantage point as viewer casts us as the beloved. These works are performative and private, intimate and flagrant all at once, a delicious mesh of contradictions. The impulse to keep images like this secret is inverted by Yuskavage’s exhibiting them; any incidental lighting ‘disaster’ is carefully mediated and meditated, loaded with centuries of symbolism drawn from the tradition of the ‘nude’, reframed. The presumed gaze, in terms who is looking at these Yuskavage women, is explicitly male – more than this, it belongs to someone with a sexual interest in the subject who poses for them. The gaze depicted, though, comes straight from the canvas. These women can see you seeing them, and the power remains theirs.

Both of the canvases described above are strange but not sinister, remarkable but not unsettling. Each measures more than 2 metres across, which seems to me not incidental. As the power ascribed to a particular Yuskavage woman wanes, so does the size of the world they’re contained in, along with our view into it. We enter in to the realm of Girlfriends when a man enters the realm of a Goddess. The presumed male viewer doesn’t negate the Yuskavage woman’s power; men who exist in the same world as them, behind the frame, seem more of a problem. Paintings of couples by Yuskavage vary in subject matter and tone, but err on the side of upsetting. ‘Ludlow Street Couple’, exhibited alongside 'Déjà Vu' and 'Housewarming' on the gallery’s first floor, measures less than 30cm in length. The abrupt change in scale necessitates our approach. Gather round, and be implicated. In Ludlow Street Couple, the body of a naked man faces us. His head is turned to the side, almost paternal as he rests his chin and hand on a much smaller female figure who is coiled around him from behind. As in 'Déjà Vu', but now with gender roles inverted, he is shown to be the protagonist by the bright colours ascribed to his skin and his helping of light, which does not deign to fall upon the little creature clinging to him. There’s something of the succubus about her, reminiscent of Goya’s Black Paintings: at once a pathetic and malevolent presence, inspiring pity and repulsion. It’s a surprisingly affecting little tableau, not least because of its scale.

We enter in to the realm of Girlfriends when a man enters the realm of a Goddess.

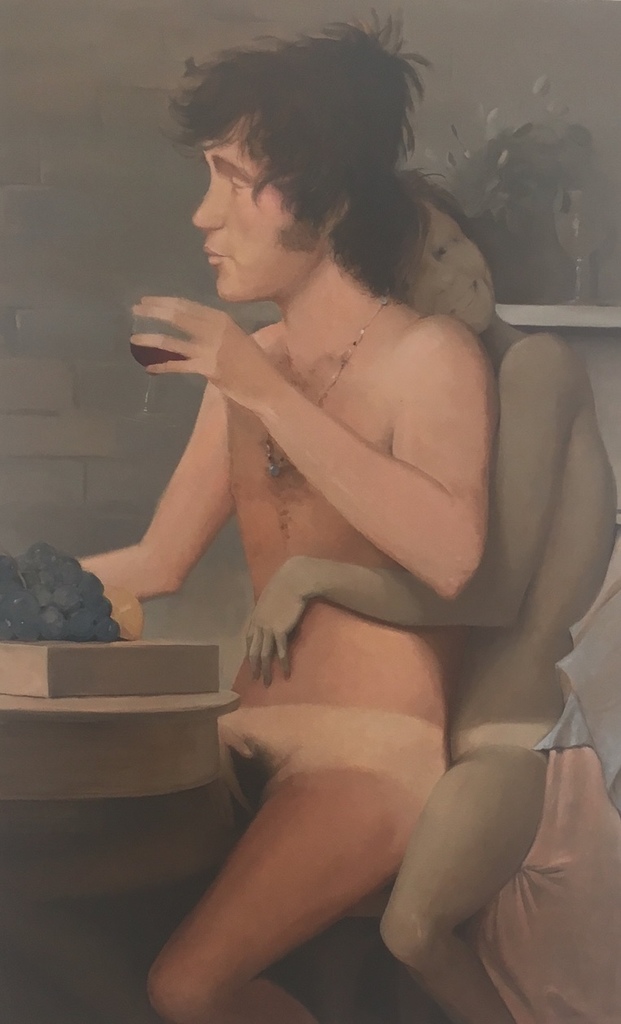

Ludlow Street Couple, and Wine and Cheese, both 2017, Lisa Yuskavage at David Zwirner

The green Girlfriend set up is repeated upstairs in ‘Wine and Cheese’, another depiction in which Yuskavage signals through colour the prominence of a male figure, front and centre, and the appendix of a girl lolling on his back, hands around his waist. She looks over his shoulder, across the room – crucially, not at us. The proportions of these Girlfriend figures are far more human than those of the pneumatic Goddesses we saw downstairs, and much smaller in comparison to their surroundings and company. Are we learning that a woman’s power comes from her sexuality? From her visibility? Or, that it diminishes when she capitulates to a man? To test the theory, we can look to two paintings from the exhibition: ‘Lavinia with Bob’ and ‘Lovers’.

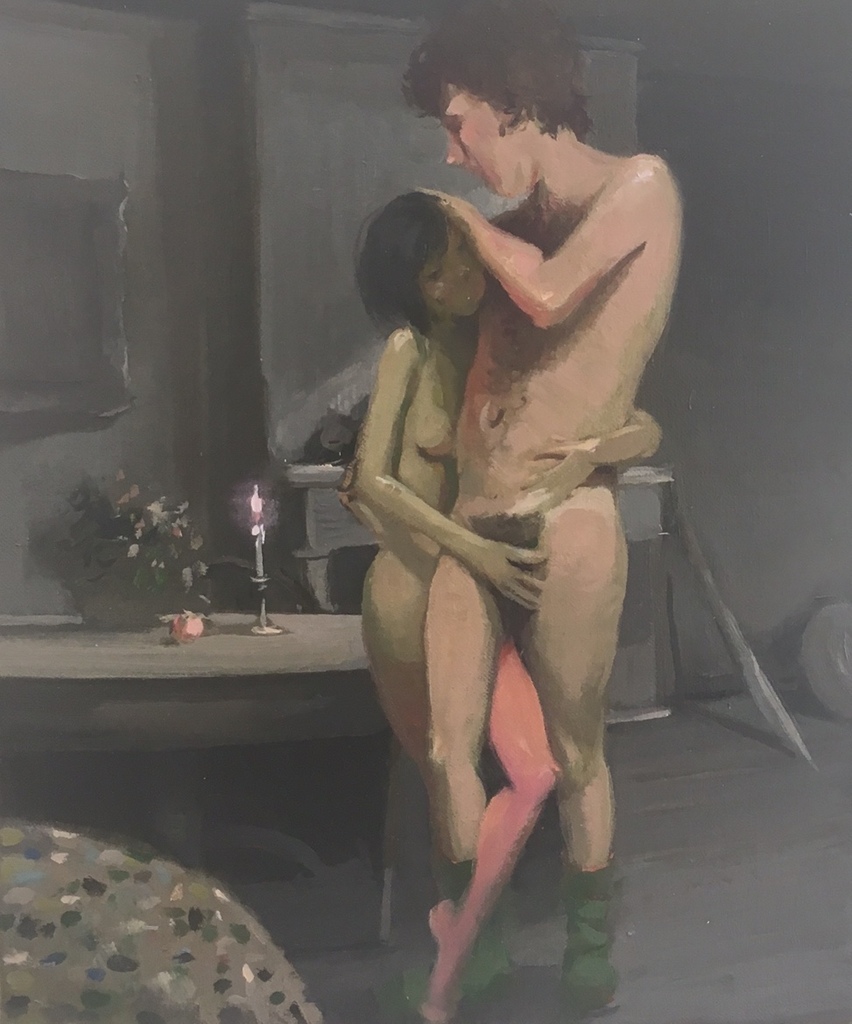

The former could be a study for the latter – its style is rougher, the paint applied more quickly and, again, we are confronted with a diminutive canvas. Nonetheless, the tableaus are almost indistinguishable. 'Lovers' constitutes a complex combination of Yuskavage’s goddesses and her darker couple paintings. Here, a woman sits on what looks like a crate, legs spread around a man standing between them whose hands are on her upper arms. The painting’s light – a crucial tool in understanding the symbolism of a Yuskavage – bathes her, while the male figure remains in shadow. Looking over her shoulder, she meets our eye with one black dot. Although her skin resembles that of the green girls in colour, it is afforded all the high-definition detail of the goddess pin-ups at the exhibition’s opening. She is fully realised. She is aware of us, and the moment we’ve interrupted is hard to interpret – particularly in terms of the power dynamics behind it. Her lover outside the canvas, we observe her with her lover inside. She is Girlfriend and Goddess both, looking outside her world and consumed by it.

Lovers, 2016, Lisa Yuskavage at David Zwirner

Lavinia and Bob tell an altogether more tragic, and less ambiguous, story. To lay out the scene in broad strokes, it is almost identical to its parent painting described above – but the devil’s in the detail. Again, a female figure sits with her body facing away from us and towards a man, head turned over her shoulder. This time, though, she does not look out. Instead, the shadowy male entity holds tight to her upper arms in what seems now more like coercion than affection or passion, and his gaze shoots straight into our own. His vision, like the girl’s in ‘Lovers’, extends only to one black dot in place of an eye. The paintings are displayed on different floors of the gallery, and so direct comparison is difficult to draw before examining them one after the other in photographs. Nonetheless, they could almost stand for an exercise in the subtleties of Yuskavage’s visual language; rather than a question of who’s looking in, examine the gaze coming from the work itself.

By Emily Watkins

Rather than a question of who’s looking in, examine the gaze coming from the work itself.

Lavinia with Bob, 2016, Lisa Yuskavage at David Zwirner