Art as Moral Compass?

When we look to art to tell us how to live our lives, we ask of it much less than it can deliver. Art - visual, literary, cinematic, musical - as moral compass is a very tight criterion for what we deem worth looking at or listening to. In the middle of a cultural earthquake of political correctness, identity politics and upturning the social order, art is frequently falling foul of a new zeitgeist which demands moral impeccability. Now, it's important to say early on that I'm not arguing with popular culture's new orientation; on the contrary, social media activism and a newly frosty climate for sexual predators, racists and bigots is wonderful news. Rather, I'm arguing that the attitude accompanying the movement - perhaps overcompensating as a new world-view finds its feet - is seeping into areas of culture where it does not help the cause.

Art is frequently falling foul of a new zeitgeist which demands moral impeccability.

There are lots of examples, reported hysterically by the right-wing press, which ostensibly illustrate this very neatly. If nothing else, a trigger warning for suicide on Romeo and Juliet is a Spoiler with a capital S. One could argue that allowing students to opt out of lectures on potentially distressing subjects is cruel rather than kind: after all, an education is supposed to prepare you for the world after the cocoon of university rather than freak you out about it. Trigger warnings are being applied to texts, films and criticism for topics including 'underage sex, homelessness and religion'. In January 2017, Glasgow University warned their theology students about the graphic content in images of the crucifixion. Quite aside from anything else, these kids will be shocked when they emerge from the chrysalis into a world brimming with all of those things and worse.

Why shouldn't people strive to exist somewhere with softer edges? Sure. The parameters someone applies to their own interactions with the world are none of my business. What does strike me as tricky is when topics or their proponents are not just prefixed with a warning but kicked out of the conversation all together, thereby striking them from the collective record. Again, that's not to say that I agree with the - frequently deplorable - opinions of people shouted down by twitter mobs. What does seem important, though, is that they are allowed to speak and be argued with as long as what they're saying doesn't fall outside the realms of legality.

Go, fight, think, win. Otherwise, the world will be made of Ladybird books.

There are undoubtedly balances to be redressed (trigger warning: understatement). White straight men have been running the show since time immemorial; their power floats in the air we breathe, the language we use, the social norms we aspire to, the assumptions we make about ourselves and others, the kind of people we deem valuable or disposable, the way we move, the things we believe ourselves capable or incapable of; all of this, then, is only compounded when the voices which have been dominant so long are granted time to speak over all the others for the umpteenth time. This understanding is crucial to any kind of advancement. We cannot allow this conviction, however, to steamroller any opinion which moves contrary to it. Instead of categorically silencing the old, move to amplify the new.

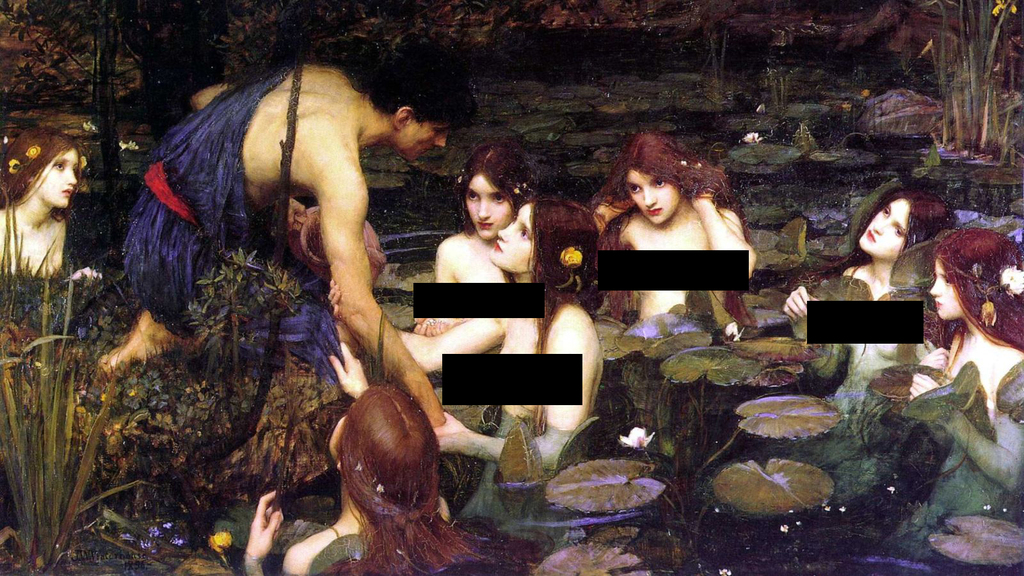

Literature is not only made of holy books. Nabokov wasn't advocating hebophilia and murder when he published Lolita; Nick Cave isn't urging you to mass shootings in The Murder Ballads; Harper Lee wasn't pushing for institutional racism when she published To Kill a Mocking Bird. Just because things are upsetting, it does not mean they aren't worthwhile. Even legitimately unsettling things - think of the Marquis de Sade, author of 'the most impure tale ever written' - are redeemable, if we ask of them what they were made to do. It's ok for things to be uncomfortable. It's ok for things to exist outside of 'right' or 'wrong'. It's healthy to understand that other people are just as convinced of their beliefs as you are of yours, and important that we learn to express ours not only within a supportive echo chamber but against an adversary. If it makes you furious, if Balthus' 'Therese Dreaming' (recently subject of a petition to be removed from public display in the Metropolitan Museum) prompts a difficult conversation about consent and agency and the male gaze, all the better. Go, fight, think, win. Otherwise, the world will be made of Ladybird books.

'Therese Dreaming' is an interesting one, its potential censorship subject to a myriad think pieces. Lauren Elkins' fabulous article on the matter for Frieze championed the right of art to 'unsettle', but also strove to reconcile the painting's subject matter with a new argument that it depicts female agency, rather than objectification; power, rather than victimhood. Again, I'm not interested in arguing whether or not this is 'true' (as though something so eminently subjective ever could be 'true' or 'false'). I'd argue that its virtue or deviance is not the point. We can let terrible things exist; they always will.

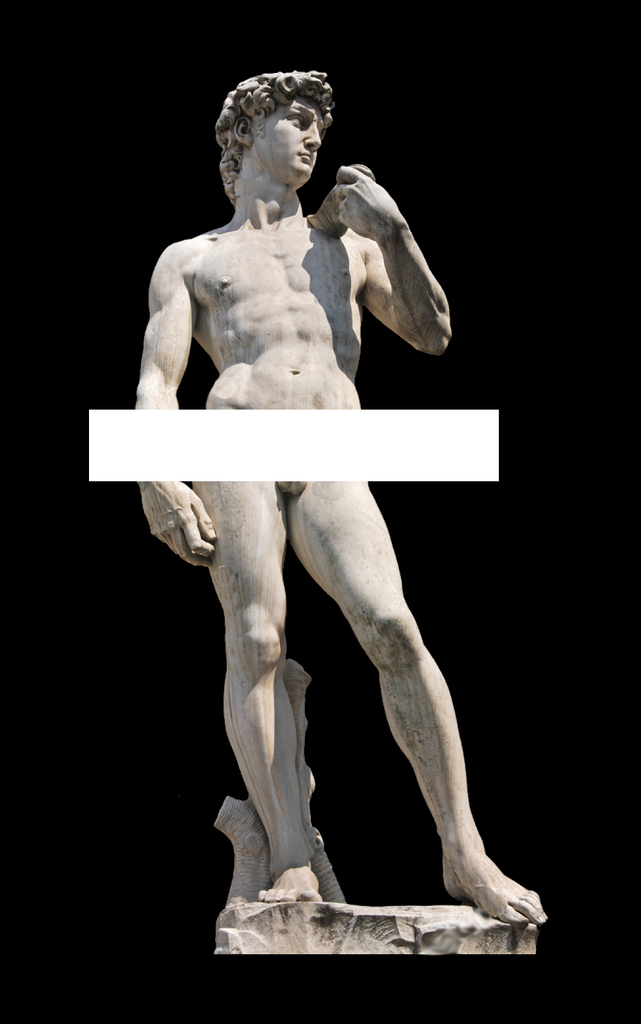

Art offers an alternate prism through which to examine reality, free from moral trappings. We don't have to redeem everything problematic, or problematise everything with the assuredness of a mathematician solving an equation. Art is necessarily something other than good or evil. More than this, and if we remove images like Therese from public view, we lose something more than our sense of what art is for: we shed touchstones for discussing history, artefacts from a world not long eclipsed which speak to where-we-have-come-from and not only where-we-want-to-be. The ban on Mein Kampf in Germany was lifted in 2016, when it quickly became a best seller. Rather than prompting a new facist uprising, the book's recirculation means that people can engage with material which shaped the history of Europe. Know thine enemy - it's when you ignore them that things get really frightening.

Make more art - but remember that didacticism is the least interesting work it can enact.

In the midst of a politics based on identity, there seems to be a difficulty in separating a creator from the product of the creative process. Roland Barthes famously claimed that 'the author is dead' - i.e., the biography of an artist is the least interesting thing about their work. Texts and canvases can be thought of as autonomous, however titillating the personal history of the human who brought them into being might be. If we followed the emerging logic - that a work is either tainted or beatified by our assessment of the artist's moral record or suspected intent - we'd have to stop reading T. S. Eliot (fascist), looking at Picasso (womaniser), Gaugin (racist), studying Heidegger (Nazi); I don't list these powerful white men because I think their work is in some way 'better' than that which has been ignored. On the contrary, the disproportionate time and attention they have been afforded can be chalked up to the depressing reality of an old but prevailing world-order wherein privileged voices amplify each other in a kind of hideous and inescapable echo chamber. I list them because their influence, un/fortunately, cannot be overstated. Try getting a grasp on modernism, what preceded or followed it, without reading The Waste Land.

We can't unpick these power structures without looking them square in the face, and we have to be brave enough to take the works they birth both in and out of context at once. Dismantle them, please, hurry - but we can't do that by erasure. Tip the scales not by clearing them (partly because we can't, but also because what already exists, no matter its moral status, has something to teach us) but by producing new material. Make more art - but remember that didacticism is the least interesting work it can enact.

By Emily Watkins.